In a remarkable scientific revelation, an international research team has unearthed the secrets of ancient survival hidden within a newly discovered nematode species. These tiny organisms, commonly known as roundworms, were found in the Siberian Permafrost and have remained in cryptobiosis since the late Pleistocene, an astonishing 46,000 years ago.

Cryptobiosis, a state of suspended animation, is a survival strategy employed by certain resilient organisms like tardigrades, rotifers, and nematodes. The ability to endure extreme conditions by essentially "freezing" their life processes has intrigued scientists for years. The recent discovery, led by researchers from the Max Planck Institute of Molecular Cell Biology and Genetics (MPI-CBG) in Dresden, the Center for Systems Biology Dresden (CSBD), and the Institute of Zoology at the University of Cologne, Germany, has shed light on the mysterious world of cryptobiosis.

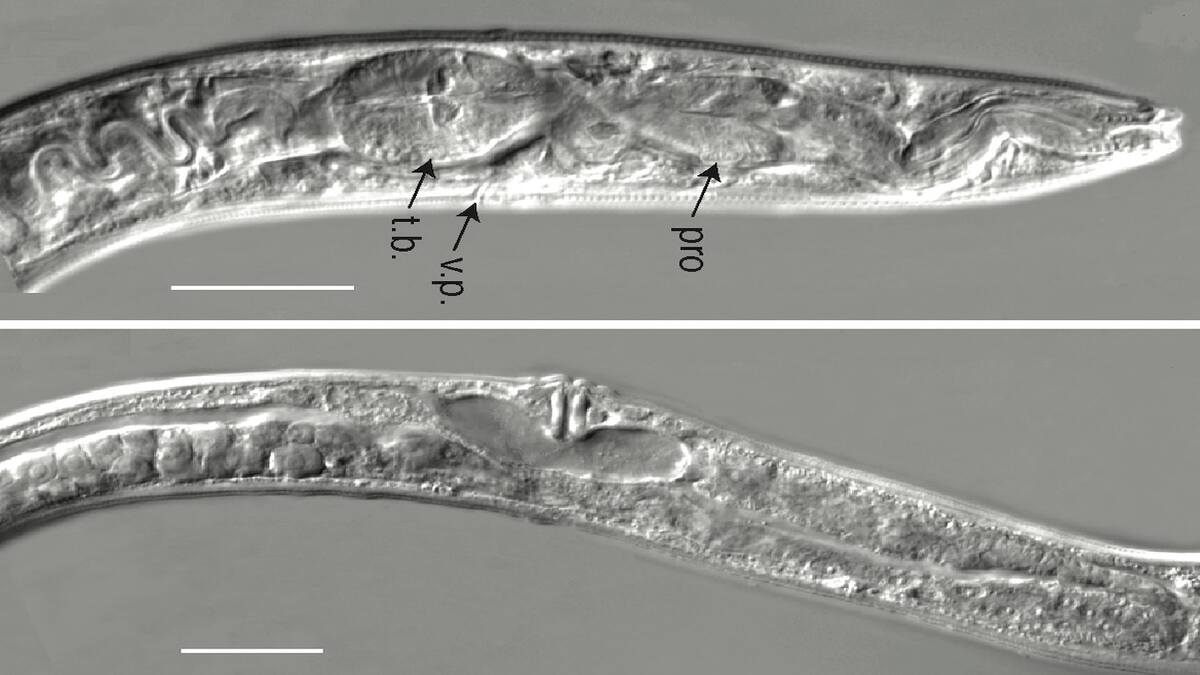

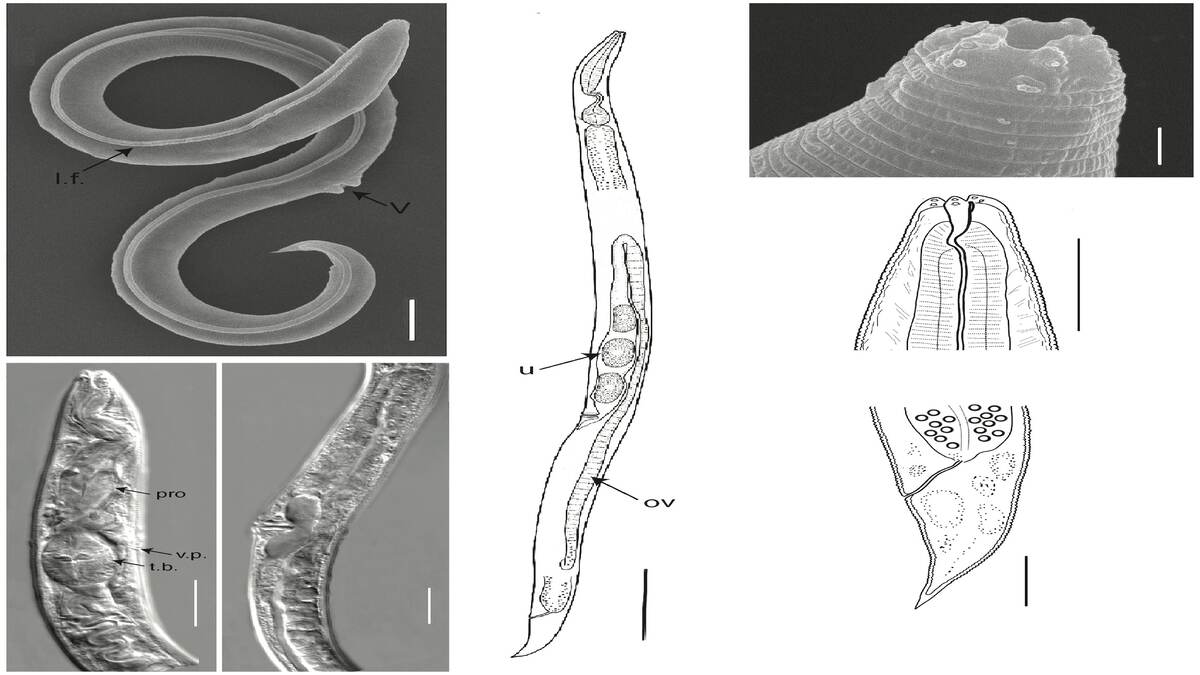

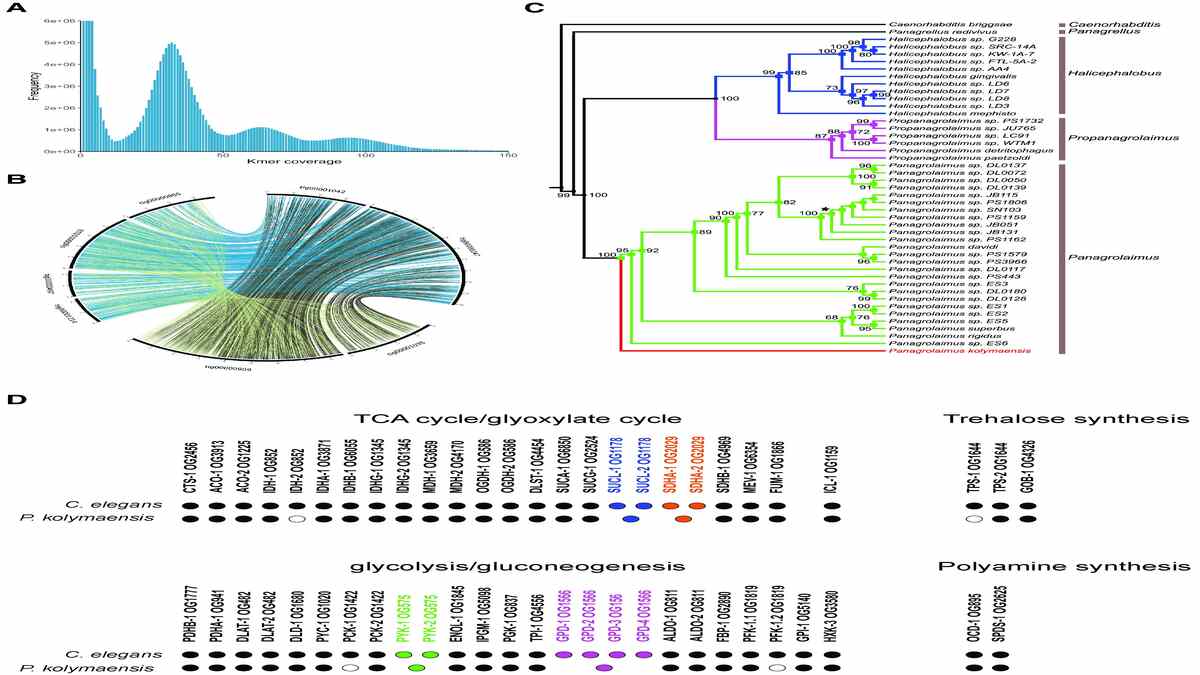

The nematode species under investigation was identified as Panagrolaimus Kolymaensis, named after the Kolyma River region where it was unearthed. The research team used genome sequencing, assembly, and phylogenetic analysis to categorize the organism as a novel species.

Anastasia Shatilovich, from the Institute of Physicochemical and Biological Problems in Soil Science RAS in Russia, played a vital role in this discovery. She successfully revived two frozen individual nematodes from the permafrost and, with radiocarbon dating, confirmed their age. Upon learning of this exciting find, the MPI-CBG research group, headed by Teymuras Kurzchalia, who has since retired, recognized the potential for collaboration and swiftly joined forces with Shatilovich's team.

How Did The Worm Survive?

Vamshidhar Gade, a doctoral student at the time in the MPI-CBG group, was among the researchers delving into the mysteries of these ancient nematodes. Gade, who is now at ETH in Zurich, Switzerland, expressed the central question guiding their investigation, stating, "What molecular and metabolic pathways these cryptobiotic organisms use and how long they would be able to suspend life are not fully understood."

Through rigorous genome analysis, the researchers discovered striking similarities between P. Kolymaensis and the well-studied nematode Caenorhabditis elegans, a widely-used model organism in biological research. Many of the genes responsible for the cryptobiosis survival mechanism in C. elegans were also present in the newly discovered nematode.

Further experiments revealed that mild dehydration exposure prior to freezing helped the worms prepare for cryptobiosis, enhancing their survival even at -80 degrees Celsius. Both P. Kolymaensis and C. elegans produced trehalose, a sugar that could enable them to endure freezing and intense dehydration.

Vamshidhar Gade and Teymuras Kurzchalia highlighted the significance of their findings, stating, "Our experimental findings also show that Caenorhabditis elegans can remain viable for longer periods in a suspended state than previously documented. Overall, our research demonstrates that nematodes have developed mechanisms that allow them to preserve life for geological time periods."

For Philipp Schiffer, a research group leader at the Institute of Zoology, University of Cologne, and co-lead of the incipient Biodiversity Genomics Center Cologne (BioC2), the discoveries hold broader implications. Schiffer emphasizes the importance of understanding evolutionary processes, where the survival of individuals over extended periods can lead to the re-emergence of lineages that would otherwise have gone extinct. Studying the genomes of species adapted to extreme environments, he believes, will offer invaluable insights for developing conservation strategies in the face of global warming.

Eugene Myers, Director Emeritus and research group leader at MPI-CBG is enthusiastic about the future prospects of research in this area. He anticipates that comparing the genome of P. Kolymaensis to other Panagrolaimus species will yield more exciting discoveries. As Philipp Schiffer's team and colleagues continue sequencing the genomes of other Panagrolaimus species, they hope to unravel further intriguing features.

Teymuras Kurzchalia offers a fitting conclusion to this remarkable study, stating, "This study extends the longest reported cryptobiosis in nematodes by tens of thousands of years." The survival strategies of these ancient nematodes could hold invaluable clues for enhancing our understanding of life's resilience and adaptation in the face of ever-changing environments.

ALSO READ| The Chinese Pompeii Reveals a Mesozoic Fight: Dinosaur vs Mammal Fossil Discovery

ALSO READ| Huge Dinosaur Skeleton Unearthed in Portugal - Check details here

Comments

All Comments (0)

Join the conversation